Have

you ever been traveling in the eastern United States or in hilly terrain or

along rivers on roads that twist and turn, divide at random angles and

otherwise wander about kind of aimlessly? Did you miss the well-behaved, simple

grid road structure as we are used to here around Sutton?

Did

you ever wonder how we came to have a structure of roads in the Midwest which so well respects

the cardinal points of the compass? Well, it turns out it was no accident.

The

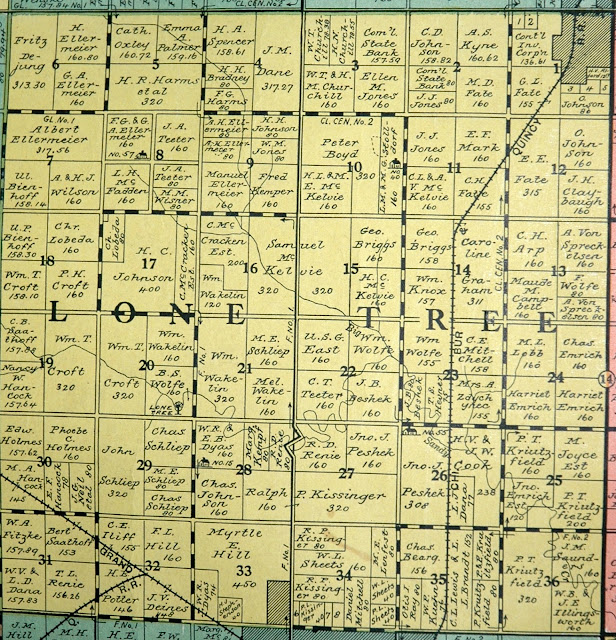

best maps to illustrate the formal layout of the landscape are local Plat Maps.

The Sutton Museum’s collection of Clay County Plat Maps is a popular target for

genealogists and other local residents researching the “old home place.” These

maps not only show rural roads but also the outlines of individual farms and

plots of lands with the names of the owners. Our earliest plat map is from 1886

and is a good document to discover or confirm the ownership of farms shortly

after this region was settled.

These

plat maps illustrate the very structured manner of defining property here in

the Midwest, a road every mile (almost) and roads that are “straight with the

world.” Not everybody does it this way. Through much of the old world and in

the regions of the original colonies there was (is) a system called “metes and

bounds” in which property lines are defined by text describing features. A

valid property description might read, “From the point on the north bank of

Muddy Creek one mile above the junction of Muddy and Indian Creek, north for

400 yards, then northwest to the large standing rock, west to the large oak

tree, south to Muddy Creek, then down the center of the creek to the starting

point.”

Another

fun example comes from the story told by Californian Frances Mayes when she

purchased Bramasole, a house on the

east slope of the Tuscan hill town of Cortona. Her agent’s translation of the

Italian conversation at the closing on the property included the words “oxen”

and “two days.” He explained that the property was “the amount of land that

could be plowed with two oxen in two days.” It doesn’t take much imagination to

think of unpleasant situations that might develop from such ambiguity.

So,

where did our system come from?

One of the first colonial era references to George Washington is a copy of a journal the teen-age George kept while working with a surveying crew on the Virginia frontier.

You

should not be surprised that Thomas Jefferson had something to do with implementing our widespread formal surveying scheme. Jefferson

had a vision of a nation of “yeoman farmers” who would fill up the middle of

the continent. The nation had a large debt in its first years with little power

to tax. One revenue source was to sell off the lands in the west. The Continental

Congress’s Land Ordinance of 1785 was the beginning of the Public Land Survey

System to catalogue the western lands for the selloff.

|

This monument marks the "Beginning Point" of the U. S.

Public Land Survey System on the Ohio-Pennsylvania

border near East Liverpool, Ohio. |

The

Beginning Point of the U. S. Public Land Survey is a monument at the border

between Ohio and Pennsylvania on the north side of the Ohio River. That

monument defined a “Meridian” line, a north-south line as a reference line for

further surveys. A “Baseline” similarly is an east-west line which, along with

the meridian line is used to accurately locate townships.

There

are thirty-seven Meridians, many with picturesque names as “Copper River

Meridian,” Mount Diablo Meridian” and “Ute.” Others are more mundane; our

nearby line is the Sixth Principle (sometimes called “Prime”) Meridian which is

the eastern border of Fillmore County.

The

marker from which Clay County land was surveyed is at on the Nebraska-Kansas

border at the southeast corner of Thayer County. The official designation for

counties is by “Township” and “Range.” Sutton Township is designated Township 7

North, Range 5 West of the Sixth Prime Meridian, meaning it is the seventh

township north of the marker and the fifth to the west. School Creek is T8N R5W

– eighth north and fifth west.

Townships

are 36 square mile squares in Clay County and generally in this region. Sections

are numbered in a “snaked” pattern beginning in the northeast corner with

Section 1, proceeding west to Section 6, then south to 7 and east to 12, etc.

with Section 36 in the southeast corner of the township. Individual farms are

designated by the fractions of the section so a designation of NW ¼ of Section

23, T7N, R5W legally defines a quarter section of land.

Surveyors buried and continue to bury metal markers at regular intervals providing later members of their club a "stake in the ground" when they were assigned to mark nearby legal boundaries. These markers are far enough below ground level that you may have been walking across them all your life and until you observe a surveying team begin digging, have no idea that one is there. They tend to be on legal boundaries: out in the country they will be right in the exact center of the intersections several inches down. The one near our home in town is in the middle of the alley behind the lot.

People

have one of two kinds of relationships with this kind of information. Either

they know it well enough to know that the preceding was a trivial explanation,

or they don’t know what I’ve been talking about and now know only that there is

some complicated way of describing land. Either way, we’re good.

The

historical society has the following Clay County Plat Maps. You are welcome to visit

us and take a look.

The

earliest map is from 1886 by Davy & Dunlap of Lincoln. Our copy has the

signature of I. N. Clark, Sutton’s early developer on the inside cover. This

set of maps is also online at NE Gen Web Project

We

have other maps sets from 1908 (Geo. A. Ogle & Co.); 1925 (Farmers State

Bank, Saronville); 1937 (Franklin Map Co.); 1956 (Clay County News); 1963, 1974

and 1986 (Midwest Atlas Co.); and 2001 and 2008 (R. C. Booth Enterprises). The 1925 plat maps from the Saronville bank are posted on this blog under the label for 1925 Clay County Plat Maps.

Growing

up in the structured physical environment may have influenced us in ways we are

not aware of. We tend to give directions using the names of the directions much

more than folks who did not grow up in these circumstances. We say things like,

“Go two miles north and three miles east” when others will give directions

calling for left and right turns and generally less precise distances.

I

personally seem to have a good sense of direction but no matter where I am, I

am not comfortable until I’ve established “North” in my head. I often found

myself on business trips arriving in an unfamiliar airport after dark, driving

the rental car out of the lot and being near-panicky as I drove off in an

unknown direction. My internal bearings would sometimes assign its own “North”

and I would settle down. Too many times, the sun came up the next morning in

the south or the west and I had to reset. If the sky was overcast for my entire

visit and I never located the sun, I never did get comfortable. I still get

queasy when someone mentions Dayton, Ohio.

I

found two other consequences of this geographic system. One article on the PLSS

speculated that the U.S. surveying system is one of the key impediments to the

adoption of the metric system in this country. Another reference came from

Wichita State University where a major project is called “Meridian 6” named

after the Sixth Prime Meridian that goes through the city of Wichita.

This article first appeared in the February, 2012 issue of Sutton Life Magazine. For information about this local Sutton publication see www.suttonlifemagazine.com or contact Jarod Griess at neighborhoodlife@yahoo.com or at 402-984-4203.