Sutton’s

Wolfe School Museum operated through the 1962-1963 school year, well past the

time that most of the county’s rural schools had consolidated into “town”

school.

The

spring of 1954 saw the closing of most of the country schools in northeast Clay

County as “redistricting” changed the lives of grade schoolers compared to

older siblings and neighbors. For decades, the coming-of-age moment for farm

kids was that jump, a big jump from the eighth grade in their neighborhood

one-room school house to their freshman year in town school.

Town

school classes were typically at least twice the size of the entire rural

school student body. Thirteen-year olds found that leap daunting enough. From a

small tight-knit group of about a dozen neighborhood friends, early teens were

suddenly thrown in with a couple of hundred strangers. That was the normal

pattern for decades. Redistricting was a one-time event that put seven and

nine-year-old kids, all kids in that five to twelve bracket through the

experience.

Later

generations accept rooms with twenty to thirty classmates from kindergarten on

as a routine part of school. The wholesale change that accompanied

redistricting probably had an impact on many farm kids. Just saying.

We

take the early rural school system in Clay County largely for granted. But it

was not an inevitable phenomenon. Universal public education was the

consequence of specific public policy very early in the history of the country.

I mean really early.

We

should credit Thomas Jefferson for setting the foundation for universal public

education. We might call him a zealot on the topic. Jefferson was a member of

the Virginia House of Delegates in late 1776 in the midst of war with Britain

when he set about changing Virginia’s legal code to correspond to the

principals alluded to in the Declaration of Independence earlier in the year.

His

“Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom” is the part of that work that is most

remembered but another topic was “A Bill for the More General Diffusion of

Knowledge.” He summarized his education plan in 1781 as follows:

“This

bill proposes to lay off every county into small districts of five or six miles

square, called hundreds, and in each of them to establish a school for teaching

reading, writing, and arithmetic. The tutor to be supported by the hundred, and

every person in it entitled to send their children three years gratis, and as

much longer as they please, paying for it. These schools to be under a visitor

[i.e., superintendent], who is annually to choose the boy of best genius in the

school, of those whose parents are too poor to give them further education, and

to send him forward to one of the grammar schools [high schools, in effect] of

which twenty are proposed to be erected in different parts of [Virginia], for

teaching Greek, Latin, geography, and the higher branches of numerical

arithmetic. Of the boys thus sent in any one year, trial is to be made at

grammar schools one or two years, and the best genius of the whole selected,

and continued six years, and the residue dismissed. By this means twenty of the

best geniuses will be raked from the rubbish annually, and be instructed, at

the public expense, so are as the grammar schools go.”

Jefferson’s

bill did not pass but he was able to implement bits and pieces of that

philosophy and was recognized for his groundwork as modern public education in

this country took shape in the 1830’s.

I

hesitated to include that quote but could not resist, for several reasons.

First, it illustrates that Jefferson was thinking past the moment, the

Revolutionary War, to consider how to construct the new country if the war was

successful. Second, Jefferson planted the seed that society had a

responsibility for basic education even of children of the poor. Latin? Sutton

High taught Latin into the ‘ 60’s.

There

are a few other things that reflect how certain words were used and defined 225

years ago. “Genius”, “residue”, “raked” are a few.

It

is important to remember that Jefferson and the Founders did not make up the

philosophical foundations of public policy out of thin air. These were the

educated “elite” of the day with at least one common trait: they read. Various

positions of society’s relationships and public policy had already been thoroughly

discussed, debated and the talking points were published decades and generations

earlier, mainly by Europeans: Locke, Rousseau, Mill, Montaigne and several

Greek and Roman thinkers.

A

lot of useful discussion happens when smart folks ponder issues over more than

2,000 years. Those seeking public office are well advised to understand, or at

least be familiar with some of that discussion.

Jefferson’s

direct contributions to our universal public school system began very early

when he headed on a committee in 1784 working out the land management scheme

for open western lands. (Open in the sense of unpopulated, disregarding

indigenous people, as they were.) That committee originated the concept of

parceling open land into ten mile squares further divided into “sections”.

Surveyors later tried five and seven-mile squares before settling on six. Our

townships were just surveyor units.

The

Land Ordinance Act of 1785 provided that five of the 36 sections in a township

were reserved for public purposes. Section 16 was designated to support schools

in the township. Sections 8, 11, 26 and 29 were held back to be sold by the

government when/if the market drove up the value. (Just found that last tidbit

on Wikipedia – need to check it out.)

Didja

notice? Jefferson managed to implement his plan for public support of education

two years before we had a constitution. The Oregon Territory Act of 1848 added

Section 36 for school support.

Another

curiosity. Sections were originally numbered starting in the southeast corner

of the township and heading north using the “snake” pattern we’re familiar

with. That may be even more weird that the current pattern.

So,

how was Mr. Jefferson’s desire for universal public education implemented in

Nebraska, and especially, in Clay County? Largely as he envisioned it. His

suggestion for one school per township did not survive, perhaps due to travel

demands. Districts of from seven to nine sections became typical with four or

five schools in each township.

Districts

were numbered sequentially starting with District #1, the Corey School just

north and east of Sutton. Mr. A. A. Corey was an early settler. Sutton Schools

was assigned Number 2. Schools numbered 3 and 4, Spring Ranch and Prairie Rose

were off in the southwest corner of the county in Spring Ranche Township.

Schools

were identified both by number and a name. The name often came from the farmer who

owned the land. Some other names were descriptive, even poetic. We had

Sunnyside, Lakeside, Blue River and Blue Valley, Prairie View and Plainview,

Liberty, Pleasant Prairie and Mulberry Grove. Our Wolfe School Museum shared

their category with Carlson, Wachter, Hartley, Peterson, Kitzinger, Kreutz,

Grubb and Grosshans. There were two Nuss schools, both in School Creek Township

about six miles apart, Districts 8 and 16.

Though

some early schools were placed in Section 16, in Clay County only 71 in

Leicester and the Spring Ranch schools did. None were in Section 36 of their

township.

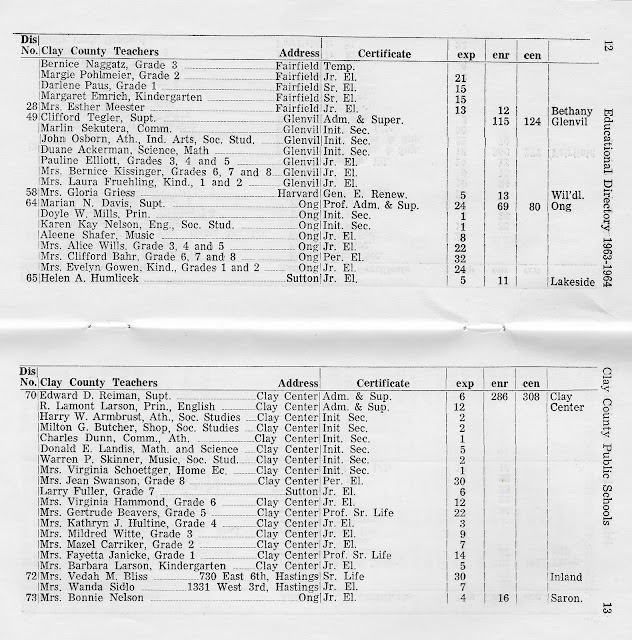

Our

primary source for details about county schools is the annual Educational

Directory that was published by the County Superintendent. We have copies from

school years beginning in 1925, ’27, ’30, ’31, ’32, ’34, ’40, ’44, ’45, ’46,

’47, ’48, ’52, ’53, ’62, ’63 and 1986. Some came from Bertha Lobeda of

Fairfield, a few from Herbert Nuss of Sutton but most are from Clarence Johnson

who served on the District 16 school board for several years. We’ve tried to

find directories from surrounding counties but have struck out, completely. We’d

like to hear from anyone with copies of these directories – we’d appreciate any

donations but would be grateful to be able to copy that data.

|

| The county superintendent published the educational directory annually. A lot of school and county history is packed into the fine print of each. |

A

common question we field at the museum is along the lines of “How many schools

were there in Clay County?” It’s a bit hard to answer.

The

question is usually aimed at the one-room country schools but let’s generalize.

County

schools were numbered inclusively from District #1, the Corey School near

Sutton to District #80, the Richview School just north of Ong. Except there is

no District #48 listed even on our earliest directory. There may have been one

that closed before 1925. Numbering then skips from 80 to District #101, the

Trumbull town school. So, there were 80 schools, plus maybe #25. There must be

a story about why numbering skipped the 80’s and 90’s. Anyone know?

Town

schools were numbered districts and should be subtracted from our list of 80

schools. Sutton is District #2; Harvard, 11; Clay Center, 70; Fairfield, 18;

Edgar, 12; Ong, 64, Trumbull, 101 and Glenvil was District #49.

The

village schools shouldn’t count as one-room country schools. They were larger

and for a time, some went through the 10th grade. Those would be

Inland, District 72; Eldorado, 67; Saronville, 73; Verona, 43; Deweese, 75 and Spring

Ranch was District 3.

So

we’ve deleted 14 schools from our list leaving 66 one-room country schools in

Clay County. True? Not true.

Harvard

District #11 not only operated the Harvard town school but also operated five one-room

country schools circling the town, each about two or three miles distant. They

appeared under the Harvard system as N.W., N.E., S.W., S.C. and S.E. indicating

the direction from town. So, we want to say that there were 71 one-room country

schools in the county. At least until the early 1940’s when the Hastings U.S.

Naval Ammunition Depot wiped out six of the county’s schools: districts 51, 61,

31, 56, 57 and 15 causing Plainview, Grubb, West Lynn, Glenwood, Weber and Lone

Tree to disappear. Now we’re back to 65 schools, post-NAD.

Our

Sutton neighborhood had nine of these schools in School Creek and Sutton

Townships. Districts 5, 66 and 8 were in a straight line, west to east in the

north of School Creek. They were called Becker, Grosshans and Nuss. District

#16, the other Nuss school, and my K-5 school was two miles west and one and a

half north of Sutton. District #1, the Corey School was just north of Sutton,

but I repeat myself.

District

9, Carlson School was in Sutton Township a mile east of the Saronville south

road; 20, called Sunnyside was on the road between sections 28 and 29 about six

miles southwest of Sutton. District 13 was the Wachter School four miles south

and just to the east and the Lange School, District 79 was just east of the Sutton

road on Highway 41.

Just

two miles to the east is the Fillmore County line and although we don’t have

any of those Educational Directories, “The Fillmore County Story” edited by Wilbur

G. Gaffney does have a map showing districts 8, 29, 31, 66, 64, 62, 89, 74, 63

and 61 were schools in Grafton and Bennett townships just east of Sutton.

The

story of these country schools was a big part of Clay County’s past which has

largely faded into the fog of history except when someone digs around in

obscure sources for an article like this. Or, until someone visits the Wolfe

School Museum on North Way Avenue in the extreme southeast corner of Sutton

Park where the visitor may trigger a distant memory of their own country school,

or more likely, try to make sense of something a grandparent once told them.

Showing

our country school to kids is a satisfying part of working with the Sutton

Museum. We are especially proud to be a part of the Sutton Schools 4th

grade Apple Valley study block when we can provide a hands-on, eyes-on visual

aid of what those schools really looked like.

This article first appeared in the December, 2016 issue of Sutton Life Magazine - www.mustangmediainc.com