You really should write down your story.

We’ve

told the story of two of Sutton’s expats in the past two articles. Both of

those men did things that were written about in newspapers, magazines and

Wikipedia. They were somewhat famous people, but even the not so famous live

lives worth remembering.

The

population of Sutton has fluctuated around 1,500 for most of its existence. So,

how many people would that be – it must be at least six to ten thousand. And each

lived a life filled with stories. And that includes you.

The

Germans from Russia organization several years ago urged members to write down

the immigration stories of their parents, grandparents and other family

members. We have a few of those in our museum. Completing these projects are

time-critical, even urgent as only a few people know the stories and the

stories will disappear as people do.

Sutton

pioneer John Maltby kept a diary including during his voyage from Boston to the

Australian gold fields, traveling rivers in India and pioneering in Nebraska.

The diary is among 13 boxes of his materials at the state historical society.

Browsing Maltby’s diary gave me a pleasant afternoon a few years ago.

Or someone’s story can be much more benign.

|

My father, Clarence Johnson, began his journal at the start of 1935. I resolved

many disagreements, misunderstandings and conflicting memories. |

My

father began keeping a journal on January 1, 1935 and wrote in it typically on

Sundays. It settled

many discussions around the supper table. If my parents

disagreed about when or if something happened Dad would announce, “It’s in the

book”, go to the appropriate volume and return either triumphant or quietly to

confirm Mom remembered better. About 50-50.

It’s

kind of cool to read what your dad wrote the day you were born.

Are

you afraid you don’t have anything interesting to say? So what? Your

grandparents had their toddler days, likely school days, they met and courted,

fell in love and were married, made a life for themselves, made a living, raised

kids and grew old. You knew them late in life. Do you have any curiosity about

how they lived their earlier lives? Doesn’t it stand to reason that your

grandkids and other younger people will have that same curiosity about all

those things you did?

If

you haven’t written down your own story, consider doing it. Really consider

doing it.

So,

what do you say and how do you say it?

Well,

you can start at the beginning. I’ll illustrate.

I

was born on June 23, 1943 to Mildred (Cassell) and Clarence Johnson.

OK,

a start. Do I know anything else about that day?

“I

was born in the midst of World War II when many common items were rationed.

Every person had a ration book that allowed purchase of sugar, flour, coffee,

meat, gasoline, tires, etc. I was born at 4:45 am at the Hastings hospital. My

Dad drove back to Sutton later that day, stopping in Clay Center to pick up the

new ration book that I was now entitled to, a book of stamps authorizing my

parents to buy more items than they could the day before.”

|

You likely have lots of family pictures, perhaps labled

but maybe not. A little effort on your part to label and

preserve photos will earn the appreciation of your

offspring, and can add a chuckle to your day. |

Isn’t

that a story worth preserving? It’s personal, but it does provide a bit of

background. You certainly have similar stories.

You’ll

want to mention your grandparents and other relatives. You don’t have to go an

entire genealogy thing; that’s another project. But you should record what you

know about those people.

For

instance:

My

grandfather David Cassell died two years before I was born. My mother told me

that on Sunday morning he would shave, take a bath and smoke a cigar, and that

was the only occasion he did any of those three things.

We

only have a few pictures of the man and that little piece of information is

what I think of when I see those pictures.

My

other grandfather died when I was six. My most vivid memory of him was the day

he ran over my toy truck I’d left in the driveway. I didn’t learn the meaning

of “distraught” until years later, but when I did, I knew that’s how Fred

Johnson felt that day. (He got me a new truck.)

Your

story will be better focused and easier to write if you identify your audience

first. You will be one member of that audience yourself. Memories are fragile.

Once you start recalling little details, more will come back, but not always.

I

kept a good journal and took a lot of pictures on a lengthy trip to Europe 14

years ago. Using that journal and the pictures as a reminder, I can reconstruct

many of those days, a thing I know would not happen without those clues.

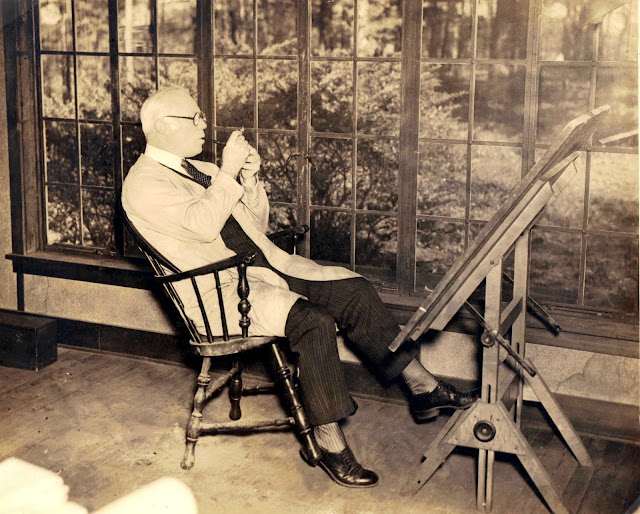

|

Your relatives are a part of your story, don't leave

them out. This is my uncle Mike Cassell who

worked in the Sutton Lumber Yard for... ever. |

But

you should share your story. I write for my grandkids. They don’t know it, and

I don’t require them to care. But aiming at them provides my focus.

Your

story will likely include your school days. I attended country school from K-5th

grade. That is a memory that a diminishing population has. Our Wolfe School

museum is the ultimate show-and-tell for that purpose, but our personal

memories fill out that story. Again, for instance:

Our

country school had a storm cellar dug into a hillside on the school grounds. It

was intended as a safe place for pupils in case of a tornado. The cellar was

crawling with snakes. The young teacher had asked the school board (including

my father) to clear it but it wasn’t happening. One spring afternoon she

cancelled classes and led a bunch of boys, and girls, in a snake-slaughtering

episode, ending with 42 (as I recall) snakes stretched out on the driveway. K-8

kids don’t do much of that anymore.

That

story seems worth saving.

My

contemporaries on the farm grew up while farming was in transition (isn’t it

always?). We saw the last of stacking hay, shelling corn, threshing and other

tasks soon to be altered, automated or obsolete.

My

most painful memory of growing up on the farm was fixing fence. No matter how

many tasks you worked to completion, there was always fence to fix. It was

infuriating to move back to Nebraska 12 years ago and see large herds of cattle

confined by a strand of horsehair-sized electrified wire. I spent my youth

repairing and rebuilding “miles” of four-strand barbed wire stapled to

closely-spaced buried creosote posts, railroad tie corner posts and carefully

designed gates. Where is the justice?

Your

story, the story of your life is worth remembering and saving for others. Think

of the tales we tell at family reunions, to friends over dinner or at the bar,

in letters… Scratch that, we don’t write

letters anymore. Emails, tweets and texts are not conducive for what I’m

talking about. All the more reason…

|

My grandparents took this family photo in the fall of 1911 - yes, the horses were important family members for early farmers.

My grandparents raised at least seven of their nine children in this house on the west side of Section 3 in Logan Township,

until recently occupied by Jim and Virginia Moore until it was badly damaged in a fire. I claim that my mother is in this

photo as that is my grandmother just to the right of the four-horse team and she would give birth to her ninth child, my mother

in May 1912. |

You

may have left Sutton for a time, for college, a job, even a vacation when you

had experiences worth remembering and telling about. Or you left home for

another reason.

There

is sensation I experience when I’m outside in that hour before dawn on a cool

morning with no wind and birds singing. A memory sweeps in and I’m standing at

attention in the breakfast line outside a chow hall at Lackland Air Force Base

in Texas. It’s 5:00 am, the birds are singing, no one speaks (absolutely no one

speaks!) as we take repeated single steps into the chow hall. I was only in

basic training for five weeks but that scene in imbedded and recalled when I

find myself outside, before dawn on a still day with birds singing.

Do

you have anything like that, a thing that triggers a memory? A song or a smell

or an object may do that for you. Tell that story and allow people to see that

part of you.

When

you tell your story, a lot of it will be centered on your family. Tell your

kids and grandkids about meeting your spouse, what was it that led to your

marriage, how you lived as a new family, how the kids changed that, and the

grandkids. Let your family take center stage for their portion of your life. You

will trigger their own deep memories.

You

should be willing to bare a bit of yourself. Brag about your successes; own up

to your failures. What are you most proud of; what do you wish you’d done

differently; what advice to you have for your reader (again, grandkids make a

good target audience).

I’ve

focused on the “writing” of a memoir here. There are alternatives. Make a video

or at least an audio recording. Your computer likely has a camera (or you can

plug one in). Sit back and tell your story. Choose a comfortable pattern.

Fifteen or 20 minute segments on one or two subject at each setting isn’t a

strain.

Technology

allows you to put preserve your files several ways. You could share your

memories via email or on at a common location (Google Docs). Lots of ways.

Many years ago, I sent each of my cousins a two-hour VHS tape (that’s how long

ago) where I’d described my version of our genealogy story as I had it at the

time. Should update that – the information and the format.

We

very often hear people say that they wish they’d asked their grandparents more

questions before it was too late. The onus may not have been on you to ask

questions, but on grandma to offer the answers unprompted.

If

so, then the onus is on you to offer the answers about your life before your

grandkids know they have questions. And furthermore, how are they going to know what a cool character you were if you don't tell them.

Did

my great-grandfather understand that? James Demetris Rowlison kept a journal

while with the 82nd Indiana Infantry throughout the Civil War. We

have six months of that journal.

|

| My great, grandfather's civil war journal is now reaching his sixth generation of grateful descendants. |